Classification of the arts is about finding the balance between censor and sensibility

The arts fulfil a significant role in society: to amuse, move, shock, provoke, reflect, interpret,

explain, inform, expose, comment, judge, critique and represent the world we inhabit.

Broadly speaking, they are by nature a vehicle for agitation, pushing boundaries, questioning conventions and raising controversial issues. They can also be

inspiring, uplifting and simply beautiful.

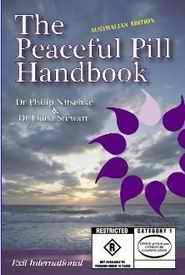

Some may view my new position, as director of the Classification Board, as one that opposes the arts. Applying relevant legislation and guidelines, the board decides which classifications to give films,

computer games and certain publications.

Yet our classification system allows for artistic freedom and that is why I continue to consider myself an advocate for the arts. It is not the role of the board to prevent the arts and entertainment from

exploring the spectrum of human behaviour and experience.

In fact, the board does not censor material at all: it must be classified in the form in which it has been submitted. Applying relevant legislation and guidelines, the board simply decides

the classifications to give films, computer games and certain publications. It does not edit material or recommend modifications to publishers or filmmakers.

|

Banned! |

Very few products are refused classification these days. Of 6097 commercial classification decisions made in the 2006-07 financial year, only 59 items were refused classification.

Australia's classification scheme is based on

the principle that adults should be free to choose what they read, hear and see with some limited exceptions, such as child pornography, gratuitous or exploitative depictions of sexual violence, cruelty or real violence and detailed instructions in

matters of crime or violence.

Classification today is complicated by the wide variation in individual sensibilities in our tolerant society. It is further complicated by technological globalisation and that standards vary so significantly across

international borders. The rapid and easy exchange of information presents a challenge for government regulation.

Standards can also change quickly in response to global events. Restrictions on new kinds of material continue to follow on from

events such as the September 11 and Bali terrorist attacks. In the past six days, amendments to the Classification Act regarding terrorist material have been passed by federal parliament: if a film, publication or computer game advocates a terrorist act,

it must be refused classification.

|

Banned! |

There are also significant provisions that protect the arts in these cases. Material is not to be refused classification if it "depicts or describes a terrorist act, but the depiction or description could reasonably be considered

to be done merely as part of public discussion or debate or as entertainment or satire".

The nature of censorship is evolutionary. The interesting challenge for the Government in formulating classification policy and legislation and the

board in determining classifications is to reflect community sensibilities, which are many and varied, and in a state of flux. Individuals' sensibilities can differ, even conflict, which makes it difficult to determine what standards are broadly

representative.

For instance, do you ban material because the majority considers it offensive, even if there is a significant minority that feels differently? Do you act in response to an articulate and vocal minority that may find certain

material offensive even though it can choose not to access it? The meeting point must allow individuals to exercise choice, yet reflect community standards.

|

Banned! |

In 1931, the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (the body responsible for rating films in the US), included in its code for industry: "Scenes of passion should not be introduced when not essential to the plot. In

general, passion should be so treated that these scenes do not stimulate the lower and baser element." Only 76 years later, scenes of passion -- and then some -- are routinely and abundantly seen on our screens.

The same organisation, now

known as the Motion Picture Association of America, recently announced that smoking is to be considered in the rating of films in the US. Films containing pervasive smoking or glamourised depictions of it may attract higher ratings. Who would have

imagined such a stark reversal of attitudes? It is interesting to note that smoking is still a legal activity, just as was passion in 1931. The widespread debate prompted by the MPAA's new policy shows how much censorship matters and the spectrum of

views it elicits.

In Australia, the commonwealth has played a role in the censorship of material for most of the past century. Under Customs legislation, before the film era, the scheme dealt with imported books: publications could be seized for

being blasphemous, indecent or obscene. Restrictions on film provided for censors to examine applications for registration of imported films, which was refused if a film was blasphemous, indecent or obscene; likely to be injurious to morality, or to

encourage or incite crime; likely to be offensive to the people of any friendly nation; depicted any matter the exhibition of which was undesirable in the public interest.

|

Banned! |

Once imported, the circumstances in which the material could be sold, exhibited or hired were determined by separate state and territory legislation. The states were expected to make sure unregistered films were not exhibited but were

not able to independently classify registered films.

Throughout the century, censorship continued to be a complex affair conducted under disparate regulations with limited uniformity. At one point, the chief censor noted that a film

classification decision involved the administration of up to 13 pieces of legislation in various jurisdictions.

Eventually, recommendations from the Australian Law Reform Commission led to the introduction of legislation in 1995 that established

the fully co-operative National Classification Scheme.

As a result of censorship reforms since the 1970s, community standards are an important component of the classification scheme and guidelines are revised from time to time with extensive

community input.

|

Banned! |

Today, the focus of classification is on films, computer games and certain publications. The board does not usually classify live theatre unless it contains video or film elements: the Spanish production XXX, by La Fura Dels Baus, which

toured Australia in 2004, included film footage of such a graphic and sexual nature the board classified it R18+.

But censorship of the performing arts, which traditionally came under state obscenity laws, has almost entirely disappeared.

Hair, the controversial rock musical that opened at the Metro Theatre in Sydney's Kings Cross on June 4, 1969, is considered a turning point. It challenged many of the established social norms of the era, with its nudity, bad language, drugs and

depictions of "free love". The chief secretary of NSW, Eric Willis, had the final say over whether Sydney audiences would see the nude scene. His reported view was that the nudity was completely unnecessary but that its brevity made its

inclusion harmless. Hair had extraordinary reviews and was an enormous success.

In the visual arts, the question of obscenity (whether a work offends contemporary community standards) has been a question for the courts.

|

Banned! |

The last blasphemy prosecution in an Australian jurisdiction was initiated by George Pell, then Catholic Archbishop of Melbourne, against Andres Serrano's photomontage Piss Christ, a photograph of a crucifix submerged in urine. It

failed in the Victorian Supreme Court, apparently defeated by uncertainty surrounding the Victorian blasphemy law and a view that the work was unlikely to cause public unrest. (We don't have laws that cover bad taste.) As it happened, the work was

physically attacked in two incidents during the exhibition's opening weekend and the director of the National Gallery of Victoria closed the show to protect the gallery and its staff.

Only last month, two controversial entries in the Blake Prize

for Religious Art in Sydney showed the Virgin Mary dressed in a burka and a portrait of Jesus Christ that morphed into an image of Osama bin Laden. Although some thought the portrayals offensive, no action was taken. Indeed, Anglican Bishop of South

Sydney Robert Forsyth suggested that we "limit the language of outrage to things that are really outrageous".

Australia is arguably an open and broad-minded place, and this is reflected in a scheme that focuses on classification rather

than censorship. The nature of the classification scheme and the principles it embodies recognise the importance of artistic and creative expression and the legitimate interests of the artists: the act provides for artistic merit to be taken into

account. And it enables potentially controversial, high impact but artistically valuable material that may not otherwise be seen in Australia to be shown under the Film Festivals Exemption scheme.

The small percentage of the board's decisions

that attract controversy shows it may be getting the balance between sense and censorbility right.